|

Decision Making

Systems

05 April 2011

You make decisions everyday

in your life – choices about what to do, make, or buy; when and which way to go

to get from one place to another; how to best achieve your needs and dreams,

overcome your problems, and meet your obligations. Life is full of choices, and

often you do not even consciously realize how many decisions you’re making.

Making decisions and solving

problems is a large part of event management, and a skill that any event

organizer must master. And like your everyday decisions, you might not realize

the scope and nature of the decisions you need to make in order to bring an

event to life and achieve the expectations surrounding it. Decision making for

events also varies from making personal decisions in the scope and nature of the

potential impact of those decisions. They can affect hundreds or thousands of

people and involve vast amounts of money. This is why the event organizer must

understand and employ effective decision making systems.

|

|

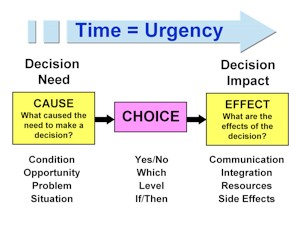

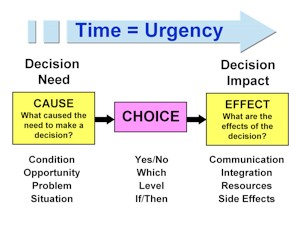

One must understand

the nature of a decision. First there is a need to make a decision

(cause), then the decision is made (choice), and finally there is the

impact that decision will have (effect).

The typical types of

decisions are:

Yes/No

(whether, only two alternatives)

Which

(more than two alternatives)

Level

(measurement, quality, or rating scale)

If/Then

(threshold or rule-based)

The amount of time

one has to make a decision can have a significant impact on the way a

decision is made and its effectiveness. |

|

|

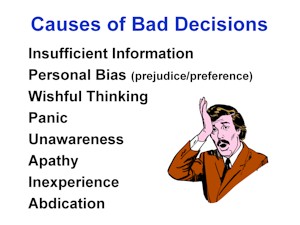

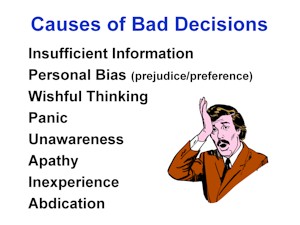

Making a decision

based on little or no information, one’s personal preferences or

prejudices, wishful thinking (or wishful listening) or panic are signs

of professional immaturity.

Not recognizing the

need for a decision is due to either ignorance or incompetence. “I

didn’t know” or “I didn’t care” might be excuses but are not acceptable

reasons.

Deciding not to

decide is still a decision; perhaps appropriate or the abdication of

one’s responsibilities. |

Keep in mind that, as a

professional, you are responsible (and sometimes liable) for the decisions you

make, the decisions you failed to make, and the decisions you did not prevent

others from making who did not have the authority to make them.

|

|

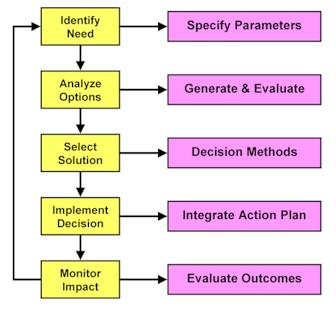

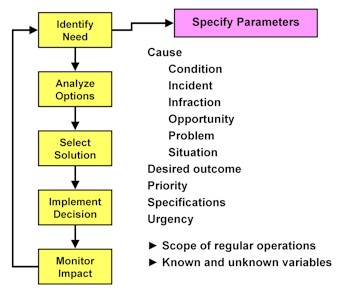

This is the system

for making decisions broken down into its separate parts. It may seem

complex and burdensome, but can be accomplished in what seems like the

blink of an eye.

It is an iterative

system that promotes due diligence. It helps one consider the variables

of the cause, choice, and effect facets of a decision, and facilitates

comprehensive and strategic thinking.

Having a structured

system allows one to purposefully move through a process as well as

establish policies and procedural tactics that ensure and improve

quality decision making for an event. |

|

|

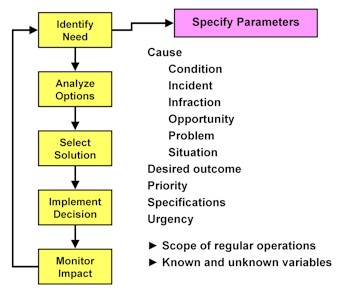

Why are you making a

decision? What went into the need to make that decision? What do you

want or need to happen as a result of that decision? How important is

this decision? How quickly must you make it? What factors must be

incorporated into this decision?

Know the Needs.

In the planning

stages of an event you have more time to spend determining the

parameters of a decision. Review the scope and typical variables

associated with this particular event project. Identify what you know

and what you don’t know, or don’t know yet, so you can plan for

contingencies. |

|

|

The 35 categories of

the EMBOK domains provide a comprehensive framework for approaching your

decision planning. As you go through each category you can determine

both the decisions to be made and the factors that go into these

decisions (see the Speaker

Integration Example).

How many decisions

do you have to make? It depends on the scope and nature of the

particular event project, but it could be anywhere from several hundred

to hundreds of thousands. You NEED a decision making system! |

|

|

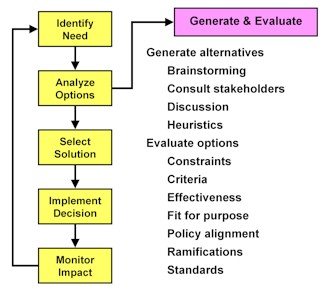

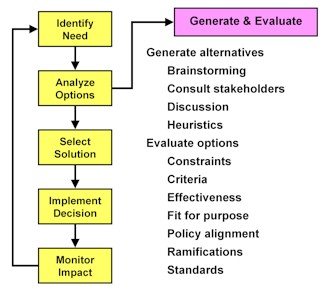

Once the need has

been defined, you must generate and evaluate the potential options for

solving the need. This is often done by gathering ideas and information

from others. Sometimes, however, you are limited by access or time, in

which case you probably rely on heuristics – intelligent guesswork based

on experience.

Consider the factors

that affect the capability of an option to achieve a satisfactory

solution. Some factors are pre-established, some are fundamental, and

some are limitations. Often there isn’t one single best solution and you

have to weigh and measure the choices. |

|

|

For example, this

chart shows the costs, trade offs, constraints, and acceptance factors

that would go into a decision about what type of conference badge to use

for an upcoming event.

At first glance one

might say that stick-on or RFID badges would be the last choice, but

that doesn’t take into account the nature of the event. For some budget

events the stick-on badge would be the best choice; an RFID badge could

be the most appropriate for a high-tech event. |

|

|

You need to know how

and by whom the decision will be made. Many of these methods use

quantitative or qualitative criteria that determine choices, for example

first come/first served for assigning exhibit spaces or vicinity quality

for site selection.

Determine who has

the authority to make the decision and if there are any conditions

placed on that authority. It might be the event organizer, the event

host or owner, a committee, or a panel of judges.

Contingency plans

need to have the if-then-when thresholds or triggers clearly defined.

|

|

|

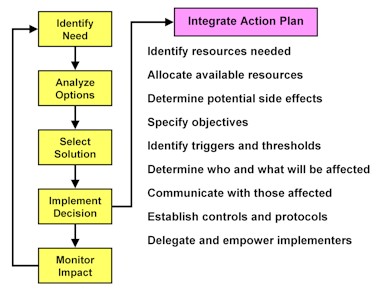

In order to

effectively implement the decision you need to recognize and integrate

the factors that affect the action plan. These include the resources

(time, money, personnel, space, etc.) and their use, as well as the

potential side effects of that use.

Communication,

clarity of expectations, and controls will be imperative, particularly

when the cause or effects of a decision involve numerous people and

activities. A single decision can create waves that spread throughout an

event project and its operation.

No change is a small change. |

|

|

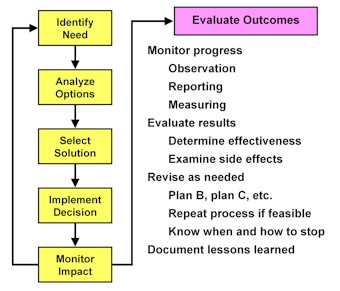

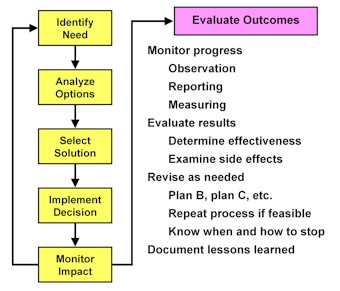

It has been said

that no decision is ever “final” (although it might not be changed

during an event project). Things change. Things don’t always turn out

the way you thought they would. Stuff happens.

You have to keep

your eye on how things are going, and if a decision is not delivering

the solution you expected, you might have to change course. This is why

contingency plans are made. This is also why the decision structure has

a loop back up to the start of the process.

Having thought

through the decision needs should prepare you to face the challenges

that inevitably occur during an event project. Make certain you learn

from them. |

|